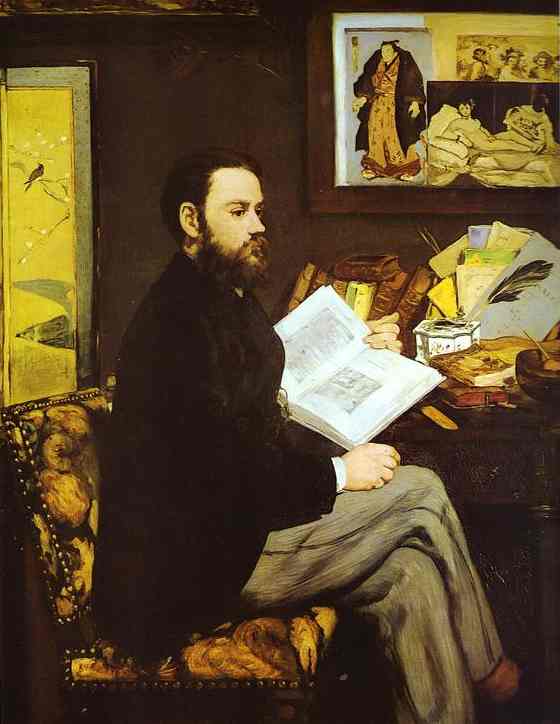

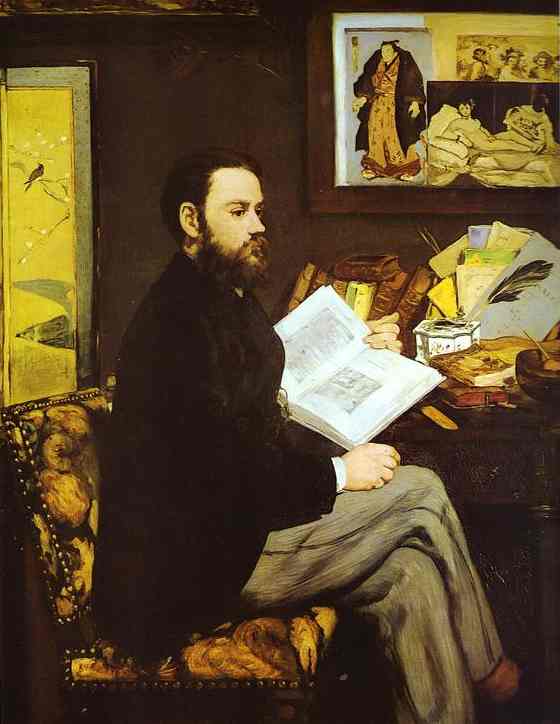

‘If you ask me what I came into this life to do, I will tell you: I came to live out loud.’ Emile Zola.

*********************

And for anyone interested in Zola’s work, try the Emile Zola society… http://emilezolasociety.org/home.html

‘If you ask me what I came into this life to do, I will tell you: I came to live out loud.’ Emile Zola.

*********************

And for anyone interested in Zola’s work, try the Emile Zola society… http://emilezolasociety.org/home.html

‘There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.’

On Monday I alighted onto the cracked, worn platform of Kirkgate station, Wakefield, having completed the first short leg of a journey from West Yorkshire to Plymouth, Devon’s most south-westerly point. A strange sight in these austere times met my eyes – builders at work. The once noble-looking Victorian station, unmanned since the nineteen-eighties and left to wrack and ruin, is suddenly being restored, if only modestly. It isn’t any great mystery. One word will probably suffice; tourists. The acclaimed Hepworth Museum is little more than a stone’s throw away.

It could be reasonably argued that the station should never have been allowed to fall into such a wretched, ghostly, intimidating state of disrepair. Let’s not go into that; reasonable arguments never seem to carry much weight. And anyway, my thoughts had drifted to the far grander revival.

For most of my life I’ve lived just a few miles down the road from Wakefield, the city where I was born. For much of that time the place was exposed to all of the problems of industrial decline and government neglect. People don’t stop loving and living, of course. Or partying. Woops! Nights out too often turned into a collective, violent drowning of sorrows. You staring at me? Pap-pop pollution wafted from hostile bars as if a sickly soundtrack to every kick in the teeth out on the street. Happy people don’t do this. People who’ve had the pride and hope sucked out of them might. Confused, full of drink, they want to take something back. For some the only route to self-respect is through their fists and tattoos.

That’s not the whole story – nothing ever is – but it’s a part of it.

Night becomes day. People shuffled or scurried rather than strode through unsmiling, endlessly rainy streets. I too moped through the sodden crowd every working day for a while, on the way to some underpaid, meaningless post.

More drizzle and drivel.

When they said the economy was doing well on the television, you knew the Wakefield district wasn’t on the TVland map. Wealth trickled down a capital bound road, winding up in off-shore accounts, doubtless. The economic tsunami of the times had left Wakefield washed up and awash with the tackiest Day-Glo trappings of consumer culture, courtesy of Poundland. Stock, Aitken and Waterman were massive, and unwittingly sum it all up. We were told it was fantastic, but you had to be a raving idiot or blind drunk to believe anything of the sort. The condemnatory images of wealth-starved communist regimes brought to us by TVland news programmes were in danger of comparing favourably to some quarters of the city. Classy. Jump on the 150 out of here.

Fast forward a couple of decades and it would be a special kind of blindman who claimed that the underlying problems had ever really gone away. And what’s going on in the wider world suggests that, in a far from wealthy city, things could get a hell of a lot worse again. Yet, unmistakably, for the moment at least, the very ambience of Wakefield has changed, and so much for the better.

Some might say there’s a reek of superficiality to it. So what if arty new stalls and a state-of-the-art shopping centre replaced the decrepit marketplace? It’s just playing to TVland illusion. And it never did anything for us. The promise of the advertisements never lasts – it isn’t meant to – and who’s got the brass for shopping sprees, anyway? The new hospital, college and bus station are vast improvements, but, by ‘eck, we’d paid our taxes and they were long overdue. Wages haven’t risen beyond the bare minimum. People were never really much better off in their day-to-day living. For a while they could access mega rip-off mortgages and credit cards and then…

Despite the approaching, threatening spectre of charity shop domination (once again), Wakefield is much improved. Its relative salubrity has far more to do with rediscovering some identity, reconnecting with its people’s achievements – regional pride if you like – than shopping mall chrome and polish, Cineworld, miscellaneous multinational McJunk, licks of paint and trendy coffeehouses. Wakefield has realised it has some spirit, heritage and standing. For miles and miles around, for decades and decades, the people’s unrewarded toils fuelled Britain’s development in times of peace and its defence in times of war. Just nip to the National Coal Mining Museum on the edge of the city. With a bit of luck and thought, you’ll get a few clues as to who really made this country.

But it isn’t all about the black stuff or dark satanic mills. There’s light and colour, too. The rise of The Hepworth and the Yorkshire Sculpture Park as international attractions attest to the area’s newfound pizzazz (sheep shit included in the case of the latter). The contours of its countryside and strident industrial vistas immutably shaped the visions of major, world-renowned artists, Yorkshire born and bred. What nearby Haworth is to literature, Wakefield – and its satellite town, Castleford – are to sculpture. And more. All those red brick back-to-back terraces can and might evoke something else. Use your imagination.

Many already knew it, but now Wakefield is doing it – boasting about its significance like every other place clamouring for attention and visitors. ‘Hey, we’re a big deal.’ In a world where image is everything, it counts. London? Paris? Madrid? If you haven’t done Wakefield and ‘one of the finest contemporary art museums in Europe’, you ain’t done it all, all of a sudden. And it’s free. Jesus, the local kids might suddenly aspire to something other than little roles, neatly packaged and boxed-in with readymade fantasies containing the ‘mysterious’ property X. I only said might.

Hmm, the government’s feverish drive to neglect the arts in state schools. Anybody would think they wanted kids to share the tunnel vision of nineteenth-century miners, slaving in the dark, hour upon hour, just for a crust. Not that art is ever the answer in itself, as something else with Wakefield connections quite horribly points out.

As I waited on Kirkgate’s drizzly platform, preparing to travel in the same general direction as Hepworth when she moved away from Yorkshire, I had in my bag a novel written by a man who, via London, also journeyed from Wakefield to the south-west. George Gissing, born in a yard just up from Wakefield’s other train station, Westgate, struggled financially as a writer in London before moving to Devon in early 1891, the year his classic New Grub Street was published.

New Grub Street had been on my ‘to read list’ for years. I first encountered the title as a teenager when I read that Orwell – a perennial first-stop for ‘serious’ young readers – had dismissed his own Keep The Aspidistra Flying for being a pale imitation of Gissing’s tome. From then on Gissing’s title periodically cropped up, always venerated but, so it seemed, seldom read by the modern world. I finally got round to owning a copy after some kind people presented me with a book voucher for my birthday (following my own less illustrious move to the south-west). Orwell, not always the unimpeachable authority some regard him to be, was, in this instance, bang on. His novel, which remains highly readable nonetheless – and which confronts life as grubby as that found on Gissing’s literary street – lacks the panoptic, crushingly-poignant scope of the Victorian masterpiece.

New Grub Street devastatingly exposes the impact of mass-production and commercialism on the literary world. Based largely on its author’s experiences, Gissing painstakingly documents the desperate privations, niggling jealousies, nasty rivalries, frustrated ambitions, failures and dubious or trivial successes of the hacks and the artists who were involved in literary production in the late nineteenth-century. The last man standing is rarely the best man; good women are always disposable pawns in the push and shove for personal gain. Talent? Does it matter? Those with wealthy families will succeed.

With no desire to keep up literary pretences, a naturalistic, curiously unobtrusive and yet humane omniscient narrator – hard-edged and genteel all at once – reveals how the commercial world slowly crushes those with a genuinely artistic temperament. And anyone else whose face doesn’t quite fit. The pages quietly bleed with so many bitter ironies that the naturalistic narrator cannot always remain aloof, occasionally reacting against injustices with cruel sardonicism – a chapter entitled ‘Reardon becomes Practical’ relates the excruciating death of Reardon, a formerly uncompromising artist burnt out by the pressures of poverty, just hours after his young son’s demise. In no time at all ‘Chit-Chat’ – grandparent of modern glossies – is conceived to profit from the quarter-educated proles. Even then we are invited to wryly contemplate Biffen, a hopelessly impractical, decent sort whose impossibly avant-garde, unsellable novel, ‘Mr Bailey, Grocer’, forms the meaning of his life until unrequited love and grinding poverty drive him to drinking poison.

Conventional Victorian society shared with our mainstream society a need for happy-ever-after endings, which Gissing’s novel provides and perverts, of course. New Grub Street generates considerable power in the way that it illustrates, with nerve-grating precision, an inevitable narrowing of possibilities, the upshot of which is that happy endings are fully dependent on discarded personal ideals and morals. The very ideal on which Victorian society thrived, however, respectable marriage, is replaced by malnutrition, suicide and death by disease for those who dared to challenge the boundaries with transgressive behaviour. From this angle, commercialism is a tyrant as ruthless as any the world has encountered.

In life Gissing’s ‘aristocratic’ artistic sensibility quashed his youthful revolutionary fervour (not that he lived to become an old man). Modern readers might sense and baulk at a related tension in New Grub Street – artistry is elitism, scornfully polarised against popular culture, quite peculiar for a writer whose early novels primarily addressed working-class life. That aside, New Grub Street is a sort of ghost-text; a dark, slow-burning, deeply absorbing artefact of the past that is able to communicate on an eerily contemporary level (despite all of the technological and cultural advances and changes in the intervening century). Gissing’s major theme touches all aspects of our world. We call it marketisation, and it is now so prevalent that – leave the arts aside – even the idea of universal healthcare is being threatened by it. New Grub Street, which betrays all of commercialism’s ugly realities, is an illuminating historical document on more than one level.

The great Romantic poets frequently experimented with, developed and revitalised conventional poetic forms. The sonnet had been largely out of favour for over a hundred years until Wordsworth, Keats and Shelley revealed their innovative prowess with the rigorous, fourteen-line structure. Shelley, the revolutionary writer of A Defence of Poetry and the propagator of the idea that poets are ‘the unacknowledged legislators of the world’, composed immaculate, poignant gems by using the genre to condense and intensify his ideas. Shelley’s best attempts compare to those of past masters such as Petrarch and Shakespeare. ‘Ozymandias’ (reproduced below) is probably Shelley’s most renowned success with the form. This reading of ‘England in 1819’ ably demonstrates Percy Bysshe composed other great sonnets.

Ozymandias

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said – ‘Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.’

Sonnet: England in 1819

An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying King;

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through the public scorn, – mud from a muddy spring;

Rulers who neither see nor feel nor know,

But leechlike to their fainting country cling

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow.

A people starved and stabbed in th’untilled field;

An army whom liberticide and prey

Makes as a two-edged sword to all who wield;

Golden and sanguine laws which tempt and slay;

Religion Christless, Godless, a book sealed;

A senate, Time’s worst statute, unrepealed –

Are graves from which a glorious Phantom may

Burst, to illumine our tempestuous day.

In 1066 – as you’ll no doubt know – the Normans conquered England. Taking complete control, the invaders made Old French and Latin the land’s official languages. As a consequence the English language lost all status, was driven underground, and kept alive by the tongues of the lower-orders.

Three hundred years later English reclaimed the linguistic centre stage. It resurfaced as a vibrant, unstable, fragmented vernacular that had once again absorbed much of another language in order to articulate new ideas, concepts and experiences. Why did English make a comeback? Firstly, the Normans lost a war to the then much smaller kingdom of France and were cut off from their domain and culture on the continent. High-ranking males on these shores started taking English wives, who nurtured their multicultural offspring using the English language. Secondly, rats (allegedly) transported plague-carrying fleas up and down the country. The officials who had everyday contact with the people developed a tendency to die, quite horribly. When the plague retreated and society began to recover, new officials were needed. Surviving members of the English-speaking lower-orders suddenly discovered social mobility – too few speakers of Old French and Latin had escaped the pestilence.

A lost war, wives, rats and socially mobile, stinking serfs. Not an RP speaker or writer of Standard English to be heard or read when the English language really was in danger of dying out and in need of saviours.

Caxton introduced printing to these isles and selected, mostly for practical reasons, a regional dialect with which to standardise text. This dialect became known as Standard English. While Caxton was struggling to overcome the problem that a land of many dialects caused a pioneering printer (rather than privilege one variety of English over another), the wealthy, educated classes – who happened to use the dialect that Caxton selected – increasingly utilised their power to assert that language use was one of the variables that defined individual worth, social status and structure. One dialect and one accent were ‘correct’, and all the others were abominations of the fields and gutters. Despite some notable dissenters – such as William Wordsworth – language was exploited to promote the nefarious political idea of superior and inferior human beings. Language use became a bedrock of the class system.

Standard English isn’t inherently bad. It’s been a fantastic asset in the development of science, education and literature. It remains exceptionally important in these fields. Nevertheless the idea that a person’s qualities can be discerned through their use of standard or non-standard language has been dethroned. The inherent value hypothesis no longer rules… It was baloney, right? And that’s not all. Try to fix a language too much and it will die. People need a versatile tool to express all the facets of their identity, join or reject new social groups, take on board new ideas, address new cultures, movements, experiences, and so on. Standard English isn’t up to it all.

Do me a favour.

Shut the fuck up moaning about textspeak. Or non-standard spellings on Faecesbook or Twatter. You’re above nobody just because you write ‘I hate’ instead of ‘I 8’ on Pretentious Sophisticated B’stard’s daily post. Do you really want to turn into one of those dull old dragons who complain to the newspapers that bad grammar and Americanisms are devastating English civilisation? If only it was so easy, huh? A few choice glottal stops and a mantra of ‘racoon in a wigwam’…

Something is tearing up the social fabric, but it isn’t dialects or sociolects, uttered or banged out on a keyboard. You might like to glance over to the Eton reunion, where they all speak ‘proper’. That reminds me. The English language doesn’t exist solely to support our economy. Stop drivelling and snivelling on about our school-leavers’ punctuation. Just because you’ve seen a hastily typed message on a social network site doesn’t mean we’re all going to be bankrupted. The ‘educated’ users of Standard English in the banks and the City have already made a colossal mess for us on that score.

Victorian prescriptivism. Stuff it up Michael Gove’s arse.

Thank you.